Perhaps in an effort to stir the pot so to speak, Corey at 10,000 Birds raised an interesting question a few days ago: Can Creationists Be Birders? The short answer is “Of course!” For most birders, the appreciation of birds does not extend much beyond the aesthetic beauty of the birds and the ability to match a bird with a name. That may be sufficient for some people just as knowing the names of their co-workers and acquaintances is sufficient, but when they’re finished, they know very little about the birds (or persons) themselves.

If you dig a layer deeper, a person can learn about the reproductive cycles and diets of the birds they watch. A person can also learn the geographical ranges of the birds that he or she knows. Or the quirky behaviors, flight styles, and habitat proclivities of those birds. Or all of the subtle hints that go into what birders call General Indicators of Size and Shape (GISS), which is often extended to include not just size and shape but any clue at all that can be used to distinguish what group or species of bird that may you glimpse.

Still, that’s all in the here and now — creationist and evolutionist alike can appreciate all of the above. Is there any qualitative difference in the birding experience between the two however? This is a very interesting question, for two reasons…First, the body of knowledge that has since formed the evidence for evolution was collected by creationists first and foremost. Creationism was still considered mainstream science during this golden age of studying taxonomy and morphology. Linnaeus, certainly no evolutionist, established the system of scientific classification that we use today, and his groupings were based upon shared physical characteristics. Only his groupings for animals remain to this day, and the groupings themselves have been significantly changed since Linnaeus’ conception, as have the principles behind them. Nevertheless, Linnaeus is credited with establishing the idea of a hierarchical structure of classification which is based upon observable characteristics — something that is entirely compatible with both the concepts of special creation and speciation.

Even Charles Lyell, who established a much older age for the Earth and paved the way for gradualism, had defended the thesis of “Centers of Creation.” These Centers offered a convenient argument for not only the periodic appearance of new species in the fossil record but also the observable differences between the floura and fauna of the continents, without really explaining how they got there. So, not only taxonomy but the observations of morphology and paleontology are compatible with either hierarchical organization of Earth’s flora and fauna.

In contrast, many of the greatest contributions to the growth of evolutionary thought sprang from observations of birds. It seems no coincidence that Darwin’s, Wallace’s and Mayr’s initial insights into the origins of species came from ornithology, and the biogeography of birds in particular. Evolution did not have a strong case until after Darwin’s Origin, which although it dealt little with the origin of species or birds, was instigated by a revelation gleaned from the puzzle of the Galapagos Mockingbirds, as Darwin’s meticulous notebooks revealed:

When I recollect the fact that [from] the form of the body, shape of scales and general size, the Spaniards can at once pronounce from which island any tortoise may have been brought; when I see these islands in sight of each other and possessed of but a scanty stock of animals, tenanted by these birds, but slightly differing in structure and filling the same place in nature; I must suspect they are only varieties. The only fact of a similar kind of which I am aware, is the constant asserted difference between the wolf-like fox of East and West Falkland Islands. If there is the slightest foundation for these remarks, the zoology of archipelagoes will be well worth examining; for such facts would undermine the stability of species.

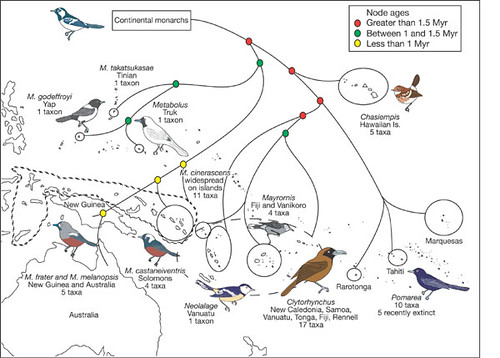

So it was here, with this odd distribution of mockingbirds (as well as a few other details of island biogeography), that Darwin first thought that Lyell’s hypothesis of centers of creation and its principle conclusion – the fixity of species – had been undermined. He also later learned that many of the other birds that he thought to be wrens, warblers, etc., were in fact finches which provided the possibility of common ancestry between seemingly unrelated “kinds.” This is the case for a variety of phylogenies, such as the honeycreepers shown in the image below – an impressive display of diversity from a strange collection of birds that appear unrelated, but bear strong resemblances to one another upon closer inspection, that betray their common ancestry.

Similarly and quite independently, Alfred Russell Wallace made the same observations first across South American and then again in the Malaysian archipelago. And summarizing a career of collecting bird and insect specimens of tremendous variety – both between and within species – he proposed what became known as “Sarawak’s Law” in 1855: “Every species has come into existence coincident both in space and time with a pre-existing closely allied species.”

This simple enough explanation also defied arguments based on fixity of species or special creation. And, knowing this biological law, you can have some kind of inkling as to where the species of bird you may be looking at has come from. Even where the relationship of one taxon to others is unclear, it follows that it is simply unclear how that particular taxonomic group originated, not that it did not originate from a common ancestor with another group at all. In this way, denying speciation closes doors to understanding where a species of bird came from, or how it may be related to sister species or clades. Some well-studied examples may help illustrate this:

- Single origin of a pan-Pacific bird group and upstream colonization of Australasia, by Christopher E. Filardi & Robert G. Moyle. (2005) Nature 438:216-219. (The paper on Monarch Flycatchers, shown in the image near the top of this post)

- The Origin and Diversification of Galapagos Mockingbirds, by Brian S. Arbogast, Sergei V. Drovetski, Robert L. Curry, Peter T. Boag, Gilles Seutin, Peter R. Grant, B. Rosemary Grant, and David J. Anderson. (2006) Evolution 60(2):370-382. (Mentioned briefly above)

- Clade-specific morphological diversification and adaptive radiation in Hawaiian songbirds, by Irby J Lovette, Eldredge Bermingham, and Robert E Ricklefs. (2001) Proceedings of the Royal Society of London: Biological Sciences 269:37-42.

So while discussing how creationists may “appreciate” something pertaining to the origins and diversity of birds can be fickle, there are clearly some things that they cannot explain with a denial of speciation. Clearly I’m not speaking to “theistic evolutionists” here, and I’m not criticizing religion per se (here, anyway). I want to challenge one specific religious view with a few puzzles from the natural world. Puzzles which speciation appears to answer, but special creation cannot:

1. How do you comprehend the ongoing debates in ornithology over adaptive “niche-filling” and geographical separation for the origins of new species?

Since Mayr’s 1942 book Systematics and the Origin of Species, there has been an ongoing debate in biology over speciation. That is, is natural selection and an empty “niche” sufficient for a new species to emerge, or do you need geographical isolation to allow for genetic drift? Most biologists tend to think the latter, because natural selection does not select for reproductive isolation, which is required for the species to remain distinct. The study of the Geospiza group of Galapagos ground finches (aka Darwin’s finches) is perhaps the best study of adaptive speciation. Ongoing since 1973, Peter and Rosemary Grant have been trekking to the Galapagos island of Daphne to track the fluctuations of disruptive selection and hybridization, and the outcome of the studies leaves a reader with the ambiguous nature of adaptive speciation. See the book Evolution on Islands and chapter 9 in particular for more on this subject (Amazon US/UK).

2. How do you understand why we say that the best places for seeing a diverse group of new birds (for the observer) is on remote islands and archipelagos?

This follows from #1: If speciation occurs and island isolation speeds it along, then most islands will be a great place to observe newer endemic species seen nowhere else in the world. The conclusion to this “If, then” statement may seem unremarkable to most people, but it is one that has puzzled biologists since the Voyage of the Beagle, and the observation that paved the way for The Origin of Species

3. And, how do you comprehend the arguments underlying debates among ornithologists and taxonomists over “lumping” versus “splitting?”

And finally, if you deny that speciation occurs, how do you follow the debates over whether separate populations of birds are the same or separate species? The ornithologists will be speaking from completely different theoretical arguments than any creationist, effectively shutting out creationists from the discussion.

The creationist can certainly identify a bird from his or her field guide just as well as an evolutionist, and appreciate its appearance and behavior, but they’re missing details regarding the origins and diversity of those birds that inform the rest of us.

Tagged: Creationism, Evolution, speciation